Wonder-Filled Science in the Flower Garden

“Hey! How did you make that sound?” Elizabeth comes running over to see what four-year-old Vera is up to.

“I’m popping the flowers!” Vera replies. “It’s so fun!”

Popping hosta flowers or opening the jaw of a snapdragon flower is a skill that has been passed down from child to child for decades in our early childhood program.

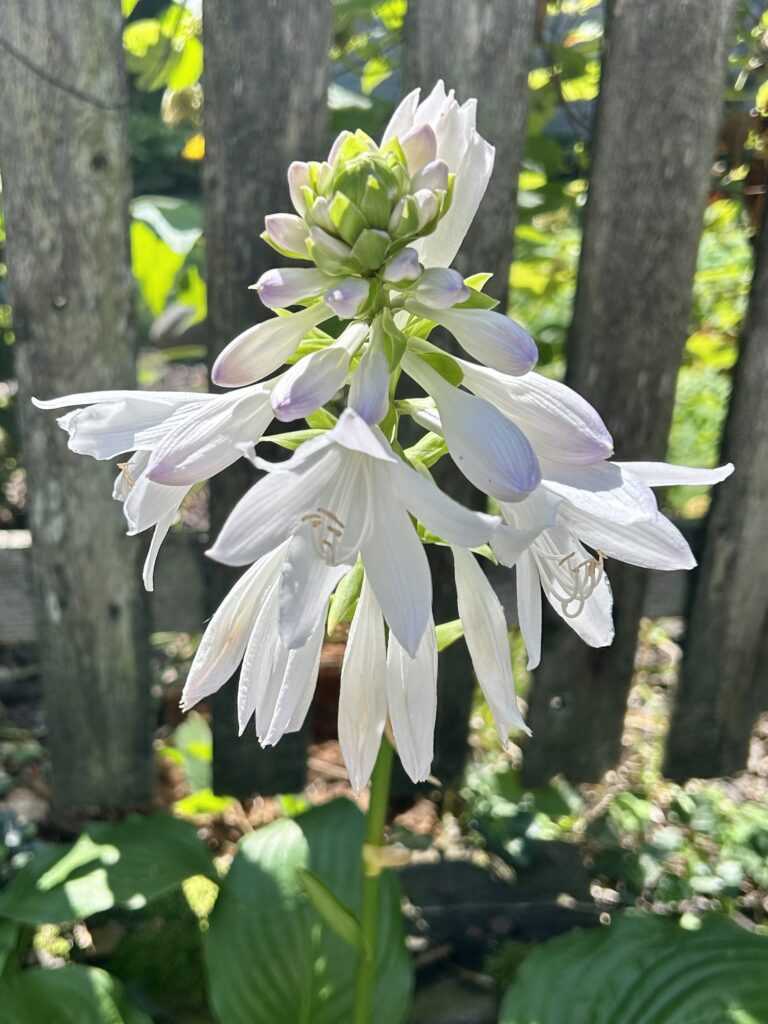

I watch as Vera scans the purple hosta flowers in front of her.

“You have to find the puffy ones,” she tells Elizabeth. “You just pinch them with your fingers and they pop, but watch out for bees!”

This simple childhood moment offers a great opportunity to capture scientific and mathematical learning in our outdoor classroom. It may look like play, but Vera is developing observation skills and looking for attributes such as “puffy” as she works her way up and down the row of flowers.

When children approach learning with curiosity and wonder—and work through their learning with active engagement with materials—they are quite often working their way through the scientific method!

“I did it!” shouts Elizabeth triumphantly. “This is fun!”

I look on as the girls observe, develop reasoning skills, make predictions and hypothesize which flowers will pop.

Science learning begins with curiosity. Observations and questions can create a climate of discovery, which is key to scientific learning. Children are natural-born scientists—and they often use the scientific method to make sense of the world.

Even our youngest friends have discovered the art of flower popping!

“Wait! Will the flowers still bloom after we pop them?” Rowan asks Vera.

“I don’t know, will they?” Vera looks at me. “Will it still get a flower if we pop it?”

“I have no idea,” I answer. “Let’s investigate and figure this out! Let’s try putting a little piece of tape below a few flowers that you pop and we can watch for a few days and see if they bloom.”

“I’ll go get the tape! Guard the flowers, Elizabeth!” shouts Vera, who is off in a flash.

We mark the white and purple flowers with blue wasabi tape and make a plan to collect data by checking on them several times a day for the rest of the week.

This is early science at its finest. A simple moment of play that sparks a sense of wonder. Children are born with an innate sense of wonder and curiosity, which prompts them to observe and question their surroundings to build their knowledge base.

Curiosity is the spark that drives the learning process. Given the time for scientific investigation, children naturally develop the critical-thinking skills that are the foundation of scientific inquiry.

As early childhood educators, it’s our job to nurture the curiosity of young children and foster the skills that will help them become future problem-solvers and innovators.

As Elizabeth and Vera ask meaningful questions, they are working to come up with their own answers by experimenting and gathering data. I simply guide their learning. Scientific investigations like this one encourage children to follow their curiosity and develop the habit of persistence as they try out new ideas, ask questions and solve problems.

These friends are making careful observations, collecting data and sharing their findings with others. When children engage in these aspects of the scientific method, they develop critical-thinking skills that can be applied to any situation.

This pedagogical method of child-led, inquiry-based learning allows children to direct their own investigations, which leads to deeper thinking and investigation.

“I think these flowers pop better in the morning,” observes Rowan.

“Maybe it’s too hot after lunch,” hypothesizes Elizabeth. “But some of them still pop.”

“Do the flowers on the bottom bloom before the ones on the top?” wonders Vera. “These up here look like they are still growing, but these lower ones look like they already bloomed.”

“Do the white flowers pop or just the purple ones?” asks Elizabeth as she spots another species of hosta a few feet away. She quickly pinches a white flower to find out.

“POP!”

“Yes! The white ones pop, too!” they shout in unison.

“Wow, Elizabeth, I have never even tried to pop a white one,” I say. “You taught me something new today.”

Both girls stop and look up at me. “Really?”

“Yes, really!” I respond with a smile. As an educator, it’s always gratifying to learn along with my students.

Much to my relief, our research that week proved that the popped buds did still bloom. I’m so thankful that the children were motivated to research this phenomenon. I’ve been popping these flowers for as long as I can remember and I, too, have wondered if my hosta-popping habit inhibited the blooms.

If you’re lucky enough to have a hosta growing nearby, take Vera’s advice, look for the puffy buds and pinch them. If you don’t have hostas in your outdoor environment, consider planting some to enhance your science curriculum. These maintenance-free perennials will re-emerge every spring and provide plenty of opportunities for measuring, observing and, of course, popping!

Check out the video below to see how fun hosta popping can be!

When popping the flowers the children are destroying the flowers. You first plant the flowers you have to use dirt, water, and the sunlight that comes from the sky. Then overtime the flowers began to grow. I would want my kids in the classroom to watch the flowers grow overtime by drawing a picture of what they see.

The children love to watch flowers grow.

What a great discovery! It is wonderful how they had the chance to explore and have this experience outdoors. I would also bring magnifying glasses outdoors and a pad and paper so they could draw what stood out to them!

children love to play in the dirt,this is a great way to teach them growth

children love to play in the dirt,this is a great way to teach them growth.

What a great discovery, I’ll be doing this with my kids. It teaches them growth!

This looks very fun for children! Children love to do things themselves and this helps them observe and get a better concept of growth and change. I would have them draw what they see.

I would implement this in the spring to teach my kids the understanding of things growing around them.

I would tie this lesson into our planting theme. This would allow children to observe growth and change.

the children will love how the flower grow and learn how to plant things plus present questions of how other things might grow.

I love the conversations you captured. I have seen hosta plants, but have never popped one. So fun!

Children have been able to participate in the total concept of planting and then seeing the flowers after they have done all their work.

we enjoyed the garden, I would love to do it again.

the children love how the garden grows and have a sense of pride

Awesome!

I love how children are allow to touch and feel the plants

I love that the children had the opportunity to touch and feel the plants

The children definitely love to watch the flower grow and participate in that process.

This would be great to help children explore the dirt and chart the process of growing

We are going to take foam cups and make our own little flowers with seeds and watch them grow into flowers from seeds that way they can see how it grows in her water and air and sunlight.

They will always remember the interest and fun they had looking and touching these flowers and the science impression will be forever.

I want to also have children touch plants and other living things that are safe. Then show them non living things to note the differences.

I think all children should have a hands on experience with plants and other outdoor items so they can observe nonliving objects and draw the differences they see.

This looks very fun for children! Children love to do things themselves and this helps them observe and get a better concept of growth and change. I would have them draw what they see.

Flowering garden is a great ideas for the science exploration.

I love the fresh ideas.

I love this idea!!

I love this

I love the idea about flowers in the classroom and the change that occurs. Not only to they get to explore the changes with their eyes but with their sense of small as well. Such a great way to explore and document living s things!

I think this was an excellent activity.

Amazing Science happens in the garden.

Love the planting for kids

Love it

Love it awesome

awesome planting with kids

planting with kids awesome

Children love hands on like planting. during this activity children can observe and see the changes. This activity is an early science lesson that is not only fun but educational.

Make a garden for the kids

Make a garden for the kids, and let them play with dirt.

The garden provides a rich learning experience in the earth, water, air science , lessons.

The process of flowers growing is a great example of photosynthesis and how light from the sun helps the flowers bloom and how in the evening they cool.

We have a butterfly garden. We not only observe plants but also the stages of caterpillar to butterfly

I love the way you encouraged/guided the children to watch and see if the blooms still happen.

Awesome! (I’ve never tried to pop a blossom on a hosta plant) I plan to try that out this summer.

I am glad you enjoyed this blog, Ann. I warn you…that popping is addictive! But oh so fun! Keep me posted next summer! Thank you!

Fun time with learning

this is good to incorporate earth water and air to teach children on plant growth

Discuss what plants need to grow and thrive. Plant flower seeds and assign a different helper each day to help water them. Observe and document as they begin to sprout, counting how many there are, which have leaves, etc. Make predictions on which will bloom first.