Small Box, Big Ideas: The Magic of Simplicity

On the cover of the October 2025 edition of The New Yorker, an infant lies joyfully on the floor, completely absorbed in play with a cardboard box. The parents, perched on the couch, watch with a mix of amusement and amazement. A simple box—not a learning toy, not a stuffed animal, just a box—has captured their baby’s full attention. This is a powerful reminder that children don’t need fancy toys or structured activities to ignite their curiosity. What they need is time, space, and permission to imagine.

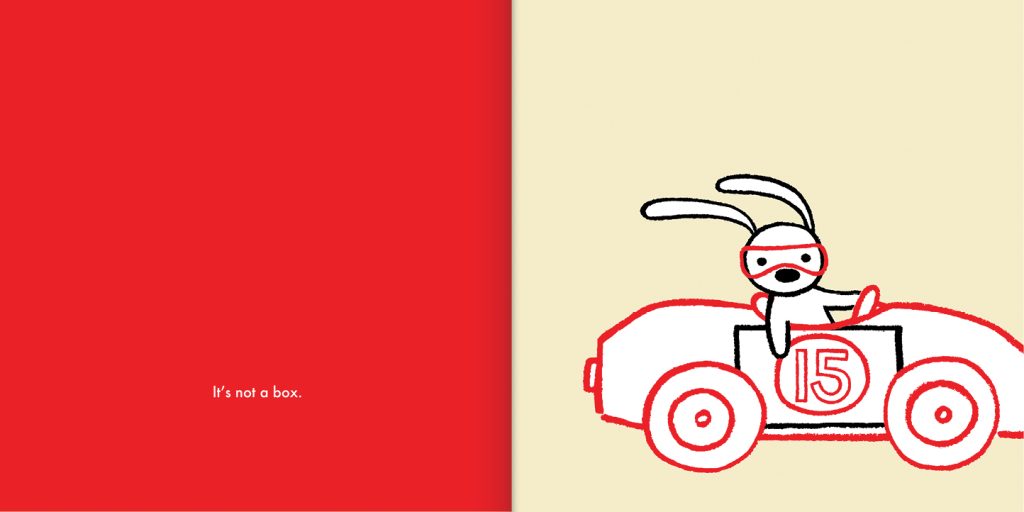

This cover pairs beautifully with Antoinette Portis’s beloved picture book It’s Not a Box, in which a young rabbit insists that the cardboard box they’re playing with is anything but a box. It’s a race car, a mountain, a robot suit, a rocket ship. Each page celebrates imagination and the child’s ability to transform the ordinary into the extraordinary.

And that transformation? It’s not just pretend—it’s science.

Children are natural scientists. They test, observe, hypothesize, and revise—all through play. When a child turns a box into a spaceship, a cave, or a race car, they are engaging in early engineering thinking:

- Designing: How can I make this box look like a rocket? Could I add wings, handles, or windows?

- Problem-solving: How do I fit inside? Will it hold my weight? What can I use to make it stronger?

- Testing: What happens if I push it, stack it, or tilt it? Does it move the way I imagined?

These are the same processes scientists and engineers use every day—but children do it intuitively, without instruction or rules. Every flap, fold, and experiment teaches cause-and-effect, spatial reasoning, and creative problem-solving. This is the magic of free play. It’s not curriculum. It’s not a lesson plan. It’s the child’s own curiosity leading the way.

A cardboard box is the ultimate open-ended toy. It doesn’t dictate how it should be used. It doesn’t beep or flash or give feedback. It just sits there—waiting. And that waiting is an invitation. A box can become a tunnel, a cave, a ramp, a robot, a laboratory, a spaceship, or a submarine. It can be stacked, cut, taped, rolled, climbed into, and transformed. Every time a child engages with a box, they’re experimenting. They’re building. They’re imagining. And they’re thinking like scientists.

In fact, the National Association for the Education of Young Children (NAEYC) emphasizes that “materials that can be used in many ways” are ideal for STEM learning. Boxes fit that perfectly. They’re not just versatile—they’re limitless.

When children decide what to build, how to build it, and when to test it, they’re not just having fun—they’re exercising their brains. Imagination activates the same areas used for problem-solving, planning, and flexible thinking. Pretend play is brain training: kids rehearse real-world scenarios, practice executive function, and build resilience.

Imaginative play is at the heart of STEM learning. Before a child can build a bridge, they must imagine one. Before testing a hypothesis, they must wonder, “What if?” Every twist, lift, and push of a box is a tiny experiment. Children experiment with angles and weight, figure out what supports the structure, and explore movement and cause-and-effect—all on their own terms.

The cardboard box was inducted into the National Toy Hall of Fame in 2005—not because it was flashy or educational, but because it was endlessly adaptable. It’s a blank slate. A launchpad. A lab bench. It’s whatever a child needs it to be.

When children decide what to make, how to use it, and when to change it, they feel ownership over their ideas. That ownership encourages persistence, creativity, and risk-taking. A child who invents a rocket ship out of a box will push, pull, and rebuild until it “flies” just the way they imagined. They’re flexible thinkers in action, testing theories, revising plans, and learning by doing.

The National Association for the Education of Young Children (NAEYC) highlights that “materials that can be used in many ways” are perfect for STEM learning. And boxes? They’re the ultimate example. Not only are they versatile, but they’re practically limitless in what they can become.

The New Yorker cover and It’s Not a Box remind us of a powerful truth: children don’t need expensive toys or elaborate lessons to learn. We need to protect time for play. We need to resist the urge to direct, correct, or instruct. Children need opportunities to explore, imagine, and create. They need freedom. They need cardboard.

If you’d like to challenge your early learners box design skills, we have an Early Science Matters lesson plan just for you! Check out Not A Box and join them in a loose-parts learning adventure!

Sandbox moat

i will be sure to do this with infants.

I willdo this with infants. in between feeding and diapering.

great!

This is an excellent use of children imagination

Great use of imagination!